Text by Catherine Wagley

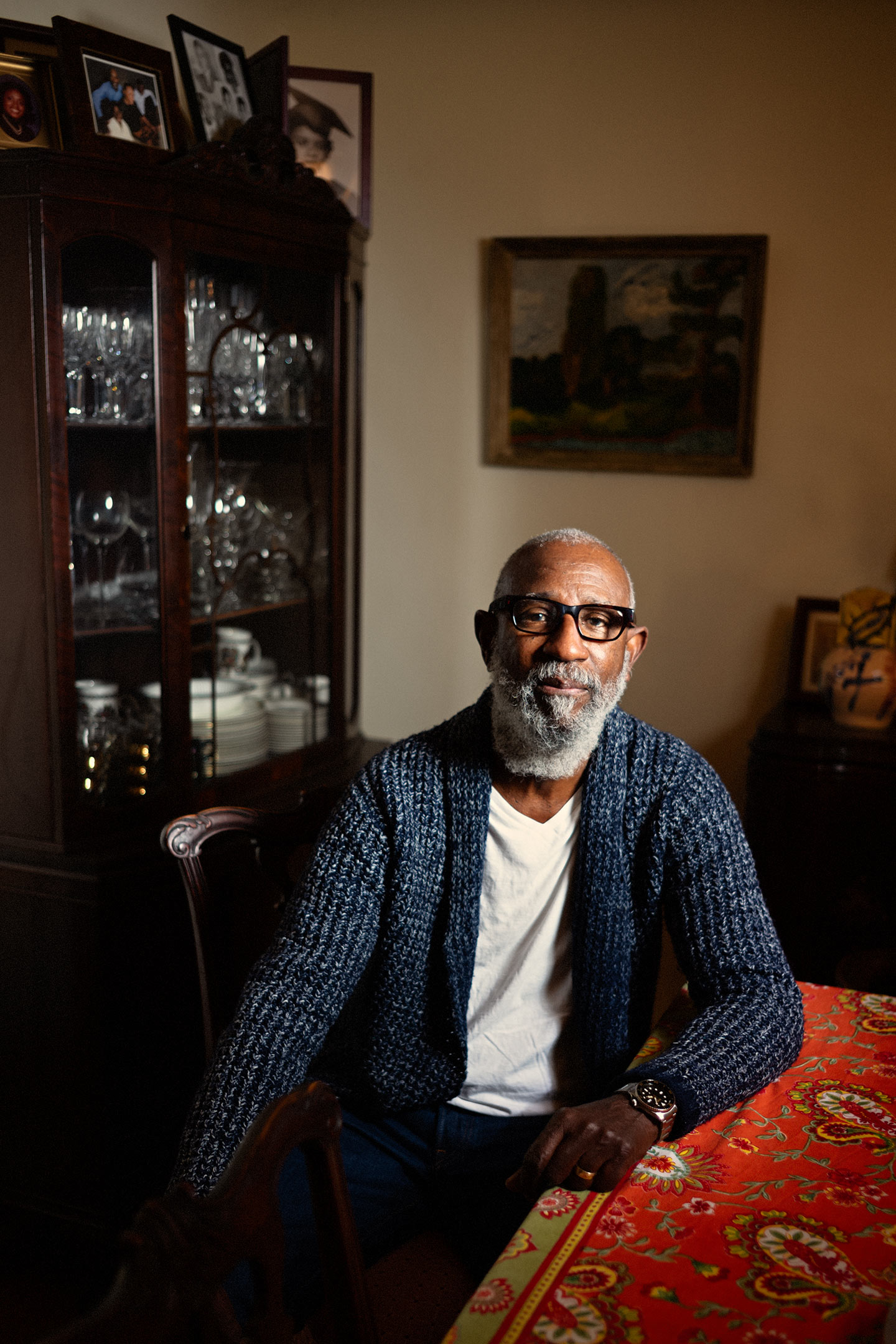

Images of Joe Ray by Sam Muller

I didn’t climb onto the ceiling-mounted swing in artist EJ Hill’s 2017 installation The Necessary Reconditioning of the Highly Deserving. But if I had, I would have swung toward a loosely painted mountain range, past sky-blue brush strokes that covered one full wall. On another wall, soft blue neon flickered: “We deserve to see ourselves elevated,” it read. Hill invited viewers to literally feel high and low as they swung from one end to another—or, like me, took it all in more quietly, as a kind of proposition for how a body can take up space. The show went up at Commonwealth and Council in Koreatown in early spring, when afternoon sunlight in Los Angeles can be particularly fierce. Sun poured in though the gallery’s skylight and large windows. Light defined this installation crafted by a young artist who often speaks about his connection to this city, home for most of his life.

There’s no need to saddle Hill with the legacy of Light and Space. His work lives, breathes, and thrives in a different context, and he never treats light, space, or perception as ideas. Rather, his work engages with tangible realities grounded in specific geography. Hill wrote, in letters published in the art journal X-TRA in 2018, about the “idyllic lawn-sprawled territories” of South Central Los Angeles and his love of specific streets (“Manchester Ave. is my main vein”), as well as what it is like to be a queer body and a Black body moving in and out of public spaces in this city. Yet even with this contrast, and even though Hill was born in the 1980s, his work conjures a salient connection to the Light and Space movement associated with the L.A. art scene of the 1960s and 1970s—especially if we look beyond the movement’s best-known highlights.

The most familiar, heroic version of the West Coast Light and Space movement took center stage recently by way of Kanye West. When the rapper met artist James Turrell, he felt a kinship: both men were “just stars,” he told GQ in May 2020. Soon, West was modeling plans for his Wyoming compound after Turrell’s skyspaces, site-specific ascetic sculptures with open ceilings calibrated to emphasize the sky’s changing colors. West even shot the video for his 2019 album Jesus Is King in Turrell’s Roden Crater, a cavernous installation in Arizona’s Painted Desert with cathedral-like light chambers that has been half a century in the making.

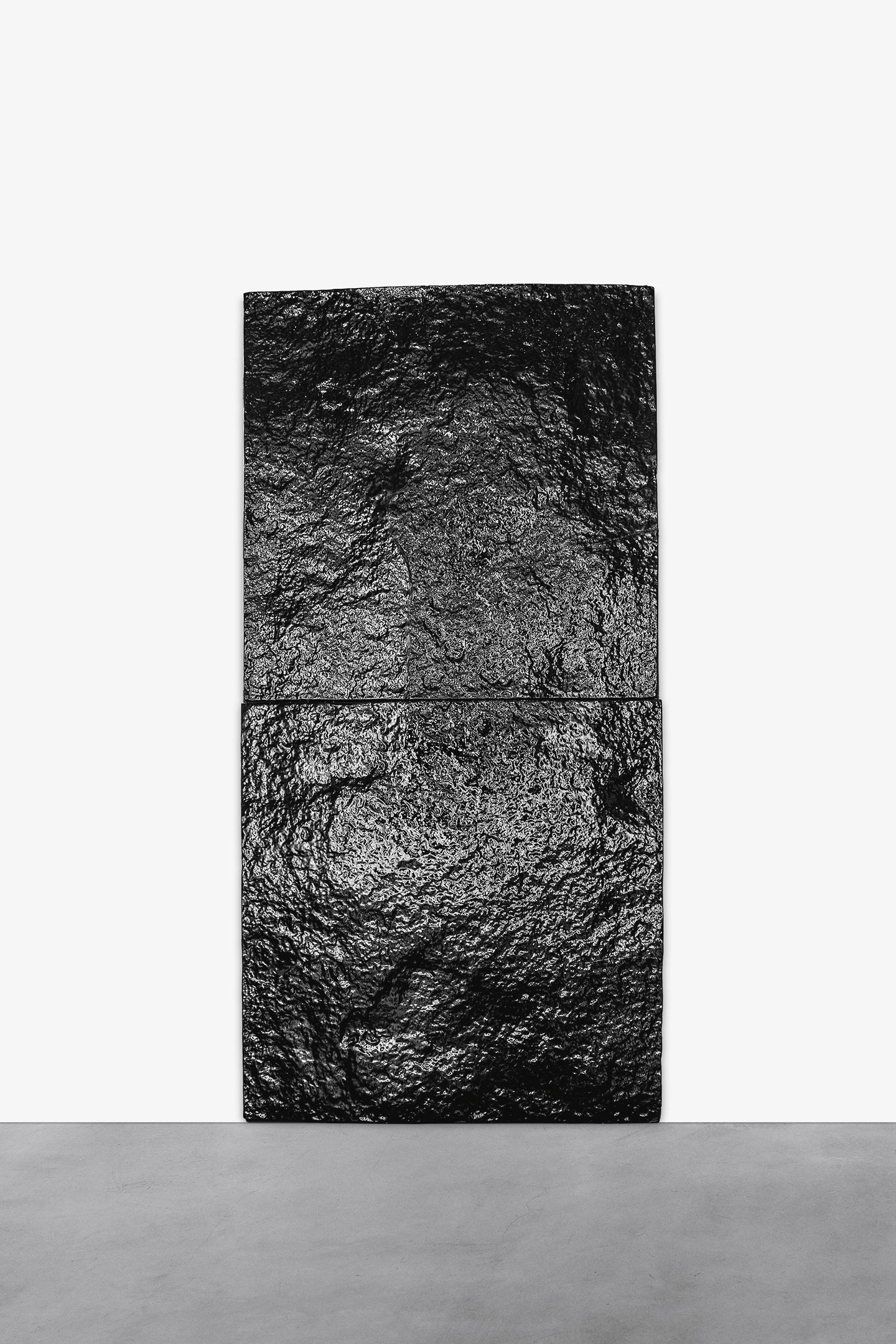

2020, by Joe Ray. Photo courtesy of Diane Rosenstein Gallery.

In 2008, when artist Evan Holloway made his polka-dot room at the Pomona College Museum of Art, he was in part reacting against what he perceived as the heroic purity of Light and Space. Turrell, one of the artists most prominently and consistently hailed as a Light and Space innovator, had recently debuted a plaza-sized skyspace on Pomona’s campus, and Holloway took the opportunity to create a less pristine but equally immersive perception-shifting room, with polka-dot newsprint covering the walls and a metal grate covering the polka dots.

“It was quite irritating to me that Turrell is often framed within a soft-core, new-age belief system,” Holloway explained in an interview published in the exhibition pamphlet. He disliked the notion of an artist who projects genius or claims to offer a transcendent experience. “I’m always in a fight with this idea,” he said, “so I publicly show doubt and contradiction and ignorance. And then, again contradicting myself, I’m so proud of myself for opposing the big boys with my humility.”

Artists associated with the movement—many of whom are still living and working—have long complicated the idea of Light and Space, a term critic Philip Leider coined in 1966 in an attempt to describe what it felt like to experience artist Robert Irwin’s curved, iridescent white canvases. As Irwin and his L.A. peers expanded into working with plastics and resin and incorporating natural and artificial light into site-specific installations, the term expanded too—though as with most art historical designations, few of the artists associated with Light and Space liked it much. Maria Nordman, for instance, has refused to participate in Light and Space exhibitions.

Historians, critics, and scholars have also long disagreed about the term’s boundaries. Historian Melinda Wortz called Light and Space artists “architects of nothingness,” prioritizing the ineffable and minimal qualities of the work. The 2007 documentary The Cool School advanced the long-held notion that artists’ obsession with plastics and light stemmed from the region’s sunniness and surf and car culture. Indeed, Nordman described her material as “the light of the sun,” though she had little interest in cars.

Curator Hal Glicksman thought that, in addition to perceptual science and aerospace technology, Light and Space artists were increasingly interested in Asian mysticism. Artist Joe Ray also observed a turn toward mysticism among his peers, but he associated it more with an interest in hallucinogens and the cosmos.

“The whole community was into the mystical aspects of making art, the alchemy,” Ray said, looking back at the 1960s in a 2011 interview with curator-critic Ed Schad. Ray, a Louisiana native who was drafted into the U.S. Army not long after arriving in Los Angeles in 1963, returned in 1967 after a year in Vietnam to find his peers preoccupied with plastics. In the late ’60s and early ’70s, he began working on a series of cast-resin and Plexiglas rings, stacking the rings on top of each other and placing a perfect round orb inside of them. “I was thinking of the circulatory system as equally vast as the celestial,” he recalled. “I was looking to latch into something other than earthly things.”

According to Ray, the Los Angeles scene he belonged to then was largely undefined. “It was in its infancy, but it was more personal than a movement,” he told Schad. The lives and work of the artists associated with Light and Space overlapped; they used similar material and even helped each other acquire it. Yet they were, on the whole, a wildly disparate group.

Ray, who still lives and works in Los Angeles, has rarely been included in survey exhibitions or catalogues chronicling Light and Space, likely because he never committed exclusively to his cast-resin experiments. Instead, he made documentary photographs of the Black Southern community in which he grew up, made paintings that straddle abstraction and figuration, and staged humorous performances, like a human car wash, for which he and his friends dressed up as the big, floppy brushes and covered themselves in white foam.

Ray’s 2017 survey exhibition at Diane Rosenstein Gallery felt like glimpsing inside the mind of an artist far more committed to understanding all kinds of light and space (cosmic, psychic, spiritual, and geographical) than to any specific material or strategy: pristine plastic spheres coexisted with colorful, gestural paintings of constellations, grainy videos and snapshots of exuberant performances across Los Angeles, and a diagram of art’s relationship to energy carefully drawn in ink.

In 1993, when critic Jan Butterfield wrote her survey The Art of Light + Space, she made some notable omissions. In the afterword, she explained she had left out Mary Corse, whom she called “an enigma,” in part because Corse made so many paintings. Corse herself, who had her first major museum survey in 2018, has never identified with Light and Space as a movement either, in part because she didn’t feel embraced by her mostly male peers in 1960s and 1970s Los Angeles. Helen Pashgian—who, along with Maria Nordman, is among the only women associated with the movement, and whose work has recently begun appearing in more major museum shows—similarly recalls feeling isolated, though she attributes it partly to the fact that she worked in Pasadena, while Turrell, Irwin, and others were neighbors in Venice.

Corse’s ongoing medium of choice is painting on canvas, which she returned to in 1968 after years of making acrylic boxes containing argon tubes. She did so because she wanted to further simplify the experience of her work. With the light boxes, she had been looking “for an outdoor reality,” she told me when I visited her Topanga Canyon studio in 2017. But she realized this reality was “not out there.” Even her dimensional experiments with light were intuitive gestures shaped by her own subjectivity, she thought, so she went back to painting.

Since the late 1960s, Corse has mixed tiny glass microspheres into her paint, the same microspheres that make divider lines on highways glow at night. The spheres announce themselves differently depending on how you approach a painting or where the light is coming from. The microspheres paintings are an ongoing, exceptionally focused undertaking: She has done variations of white-on-white (White Light) and black-on-black (Black Light) paintings for decades.

She occasionally ventures into other palettes and materials (her Black Earth series of ceramic tiles, made outside her Topanga studio using molds taken from the surrounding landscape, for instance), but primarily works in monochrome, mostly because she is still so deeply involved in exploring how slight variations in light change a viewer’s experience that she is not yet ready for more color.

Corse has also been a mentor to younger artists, such as sculptor Gisela Colon and painter Kelly Brumfield-Woods, whose own shimmering canvases take a more hallucinogenic, colorful approach to exploring perception. For Brumfield-Woods, who is Corse’s former studio assistant, Corse is an influence not just because of her art, “but the way she works with such focus and how she sets boundaries so her energy goes to her work.”

So often, conversations about historical movements pivot around influence: How has an earlier generation shaped those who came after them? But it can be equally beneficial to ask: How do artists working now shift our understanding of what came before? This is especially relevant with a movement so grounded in a place that has changed drastically yet is still defined by sprawling space and intense sun.

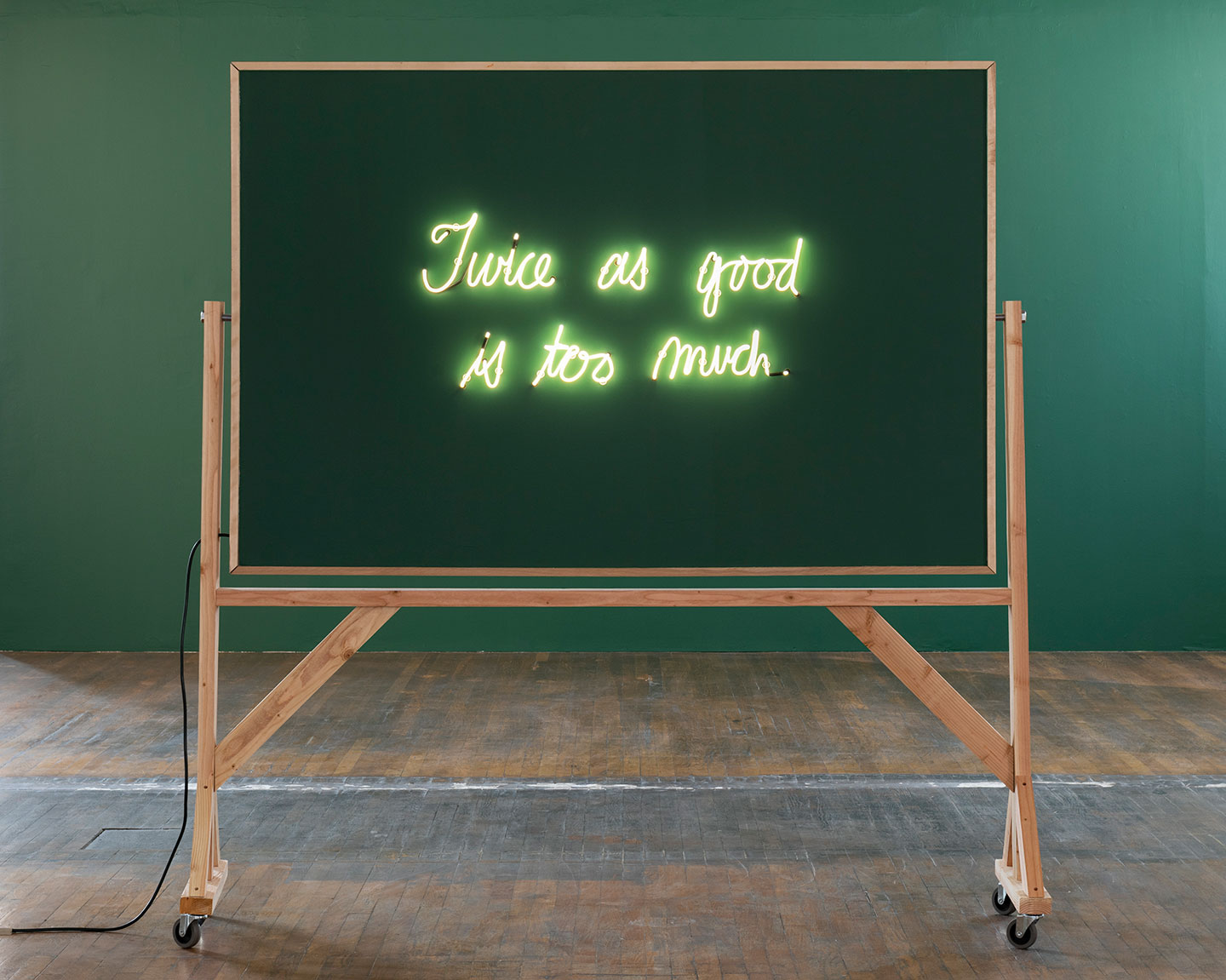

EJ Hill’s recent installation Excellentia, Mollitia, Victoria, which translates to “excellence, resilience, victory,” part of the Hammer Museum’s 2018 Made in L.A. biennial, proposed a body-conscious, durational, and intensely personal approach to light and space. Once again, walls were painted sky blue. Astroturf covered the gallery’s floor, and photos hanging around the oval room, made in collaboration with photographer Texas Isaiah, depicted Hill running laps on tracks at the Los Angeles schools he attended—capturing the hot sun, broken sidewalks, and artificially green grass. Vibrating neon script installed on the farthest wall from the door asked, “Where on earth, in which soils and under what conditions will we bloom brilliantly and violently?” For 78 days, Hill stood on a bare-bones wooden podium during the museum’s open hours, the bluish light of this text around him, questioning how we fundamentally position ourselves in relation to our environment.

The white stripes along the track reminded me of Corse’s White Light paintings and the way their shimmer contrasts the darker density of her Black Earth installations, inspired and made with the soil surrounding her Topanga studio. The installation also recalled Joe Ray’s more physical performances—like when he and two collaborators descended from a ceiling trap door during a concert, the stage lights making their shadows huge against the wall as they shimmied down a thick rope. There are so many ways to use light in space, and a looser definition makes for livelier dialogue between past and present.