Text by Christine Hitt

Images by Tatsuo Takei

A surfer casually glides his 11-foot longboard on a perfect 1- to 3-foot wave wrapping around Malibu Point. Cross-stepping to the nose, he slices through the glassy water. Dozens paddle behind him, readying for the next set. It’s difficult to imagine Southern California’s beaches without surfers dotting its shores, but at the turn of the 20th century, that was the case.

Los Angeles’ center was built 15 miles inland near the Los Angeles River. Getting to the ocean was a journey for the wealthy that required transportation by horse-drawn buggies in the 1800s until the debut of the railway toward the end of the century, around the same time that beach cities, including those at Santa Monica Bay, began popping up. Soon, the formerly isolated beaches were connected to the downtown L.A. population by railroad lines.

Henry Huntington, owner of Pacific Electric Railway, knew that the location of rail lines would affect the value of land. Having bought 90 percent of Redondo Beach in 1905—and ensured railroad track was laid to it—Huntington promoted the beach as a destination, hiring surfer George Freeth, who was Native Hawaiian, to work for him in 1907 as an attraction after seeing him surfing on O‘ahu.

“A megaphone-wielding announcer introduced George Freeth as ‘the Hawaiian wonder’ who could ‘walk on water,’” describes Matt Warshaw in The History of Surfing.

Freeth was the first surfer to introduce the sport to Southern California, regularly holding surf demonstrations five years prior to world-famous Duke Kahanamoku’s first visit to the area.

Freeth would go on to teach surfing, swimming, and water polo there.

He created Redondo Beach’s first lifeguard corps and was credited with single-handedly saving many lives at sea before his untimely death from the Spanish Flu at the age of 35 in 1919.

“They used super heavy redwood planks,” says Tatsuo Takei, photographer and author of Authentic Wave: Surf Photography by Tatsuo Takei. The 8- to 10-foot-long wooden boards resembled the traditional Hawaiian alaia surfboard and could weigh up to 120 pounds. “Then people started riding lighter boards.”

Born in Japan, Takei began surfing at 18 and chose to move to Southern California in the ’90s for its small waves that are perfect for longboarding. Cherry-picking a school near the beach, he took photography classes part time and surfed the rest of the day.

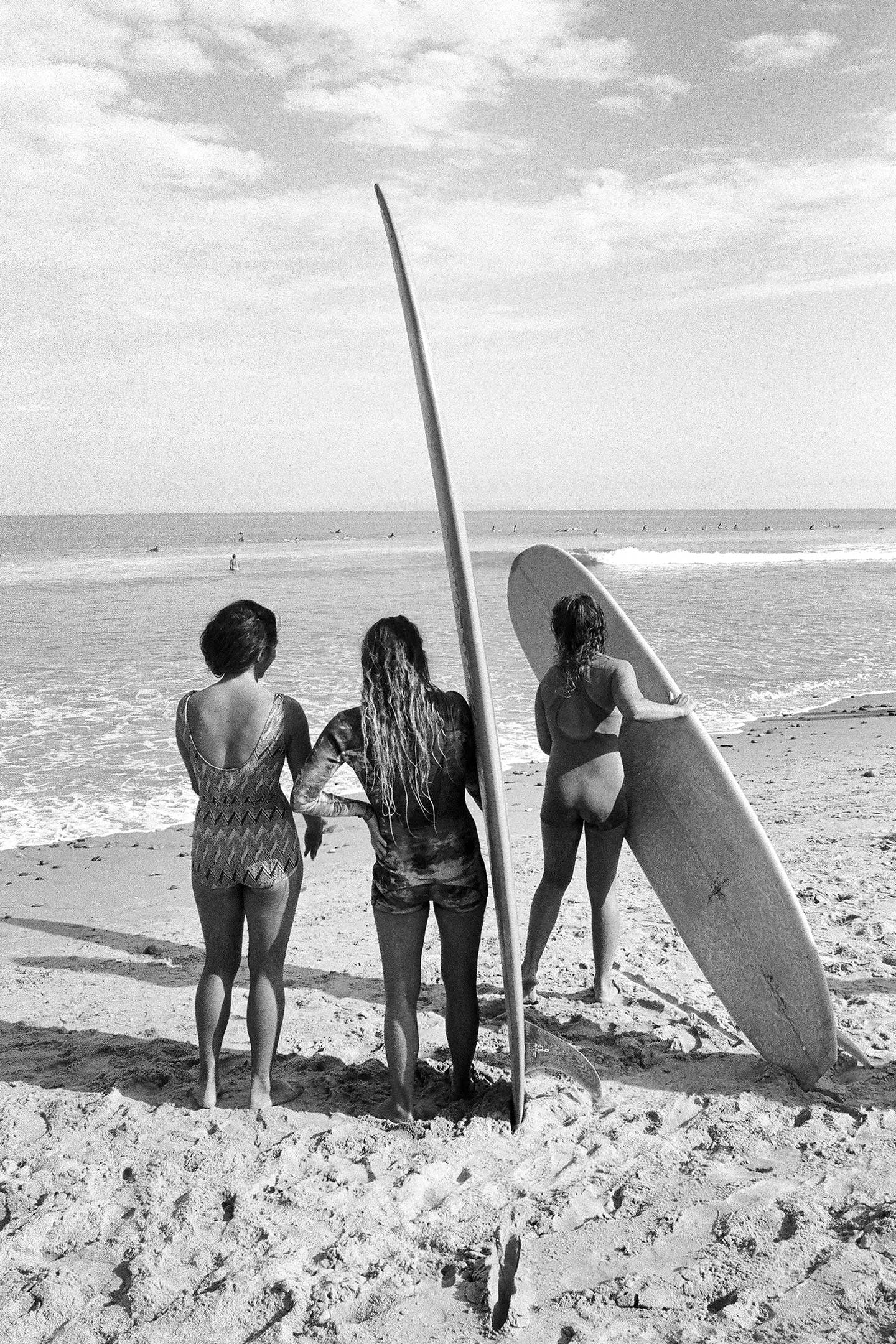

Inspired by vintage surf photography of the 1960s, Takei began taking analog film photos of single-fin longboarding, which became a passion. Authentic Wave chronicles 20 years of longboard surfing in Southern California, from 1997 to 2017, at surf spots from Malibu to San Diego.

Though Hawai‘i was the originator of surfing, California made great leaps in the sport by innovating the industry. In the 1920s and ’30s, Tom Blake produced a much lighter, hollow wooden surfboard that gained popularity.

He also introduced the stabilizing fin in 1935. In the ’30s and ’40s, Bob Simmons used hydrodynamics to improve design and experimented with lighter materials, introducing fiberglass and foam boards.

By the 1930s, the popularity of surfing exploded as the region established surf clubs, held championships, and created its own surf culture.

“Longboarders today, the middle-aged guys, they’re so relaxed and they’re easy to talk to,” Takei says.

He follows the 1960s model of photographing in black and white and likes overexposing images to create silhouettes. It takes skill and a lot of patience to produce surf photographs using film, and so he waits for a defined, glassy wave and an experienced surfer to glide into his frame before taking a shot.

“It’s challenging but it’s worth it, and I really love every single result,” he says.

More than 100 years since Freeth introduced surfing to Southern California, surfers have become a natural part of the landscape—all while photographers like Takei document the spirit of the sport through its passage in time.