The Santa Monica Airport (SMO) will shut down operations in 2028.

By Brian McManus

Images by Tim Aukshunas and the Santa Monica History Museum

It’s old now, but still innovating. We’re talking, of course, about the Santa Monica Airport (SMO). One of the nation’s continuously-running airfields, it, at one time, was also the busiest single runway airport in the world. Its life has been long, and not without controversy. In 2028 it’s set to end.

In the city’s statement about the closure, released in January of this year, Mayor Gleam Davis said, “This is the beginning of a community process to reimagine the Airport site, which accounts for an unprecedented 4.3% of the City’s land. We know this is an asset Santa Monicans care about and we want to work together to set goals and priorities to meet diverse community needs for the next several generations.”

The airport’s 227 acres will be repurposed for the development of parks, public open spaces, and public recreational facilities, and the maintenance and replacement of existing cultural, arts, and educational use on the land. New real estate development is prohibited on the land.

No doubt a noble end for a place with such a towering history.

Above: Ronald and Nancy Reagan touch down at Santa Monica Aiport. Next: SMO now and then.

Santa Monica Airport just celebrated its 100th birthday, having opened for its first flight on April 15, 1923. It was then known as Clover Field, named after famous World War I aviator 2nd lieutenant Greayer Clover, a fact sometimes forgotten to history in the rightful confusion over the name of a nearby thoroughfare, Cloverfield Boulevard, which suggests a field of green clover rather than the fallen soldier.

Over its storied past it has hosted famous pilots like Amelia Earhart and business magnate Howard Hughes, and welcomed many a president to its runway and helipad—Reagan, Trump, Biden. In the ‘40s, with the help of the war effort and Donald Douglas and his Douglas Aviation company, it employed 44,000 workers. Some years later, in ‘58, when Douglas wanted to lengthen the airport’s runway and use it as the manufacture and test site of the DC-8, he was rebuffed by city officials who feared angry constituents. So he picked up his jobs and propellers and went to Long Beach Airport.

That early squabble laid bare some of the earliest clues Santa Monica Airport’s days would likely be numbered. Namely, that the city’s residents, some of whom lived close by, would lobby long and hard for restrictions that would hobble air traffic to the point of their being no point or for SMO’s out and out closure. It’s a fight that, by the time it ends, will have lasted some five decades.

Over that span, its detractors have had the runway shortened to alleviate some concerns over noise pollution, organized groups and committees——Citizens Against Santa Monica Airport Traffic (CASMAT) and Sunset Park Anti-Airport, Inc., (SPAA)—assembled protests, and put up yard signs to persuade neighbors and passersby that SMO should go. None of their efforts, though, could match a 2009 UCLA study of the downwind air quality near the airport, which turned up elevated ultra fine pollution particles that threatened the health of lungs of neighboring communities. Once that began making headlines, outcry grew.

In a poll, some 80% of respondents favored closure.

General aviation is ready for a much-needed boost, and the benefits of electric flight, including lower noise and emissions, are particularly important to airports like Santa Monica Airport

But that paints a distorted picture. Naturally those living directly next to the airport weren’t exactly keen on its continuing, and were more vocal about its being shuttered. Truth is, most people likely seldom give the Santa Monica Airport a thought.

In fact, they may even have warm feelings about it.

They know it—and will remember it—for things other than airplanes buzzing by the air traffic control tower and hyperlocal inconveniences.

For the Barker Hangar, for instance, which has become one of the premier and most unique venues in Los Angeles. At 35,000 square feet, it’s certainly the city’s most versatile, hosting everything from boxing matches, movies, concerts, wine and food festivals and trade shows, and the Nickelodeon Kids Choice Awards. The hangar has also become a hot spot for LA Fashion week, whose runway shows by the runway are a perfect fit.

Most famously, it has become home to the Frieze Art Fair, whose Los Angeles iteration began in 2019 on the Paramount Studios lot before relocating to SMO this year. The Frieze is a giant and renowned international contemporary art fair which takes place in London, New York, Seoul and Los Angeles…at the Santa Monica Airport. Each year some 60,000 attendees vie to purchase works by some of the most esteemed and in-demand artists from past and present. It garners much coverage from the art press, and in LA in particular, features frequent celebrity sightings.

Attendees this year alone included supermodel Heidi Klum, singer Lionel Richie, tennis great John McEnroe, and Curb Your Enthusiasm’s Larry David. [Deep breath.] Margot Robbie, Elijah Wood, Christoph Waltz, Gwyneth Paltrow, Jared Leto, Catherine Keener, and Owen Wilson. In short, TMZ may want to train their prying lens away from the arrivals and departures area of LAX’s terminals and toward the galleries of SMO.

Aerial view of Clover Field Airport in Santa Monica, showing residences in the distance, 1924. Photo courtesy University of Southern California Libraries and California Historical Society

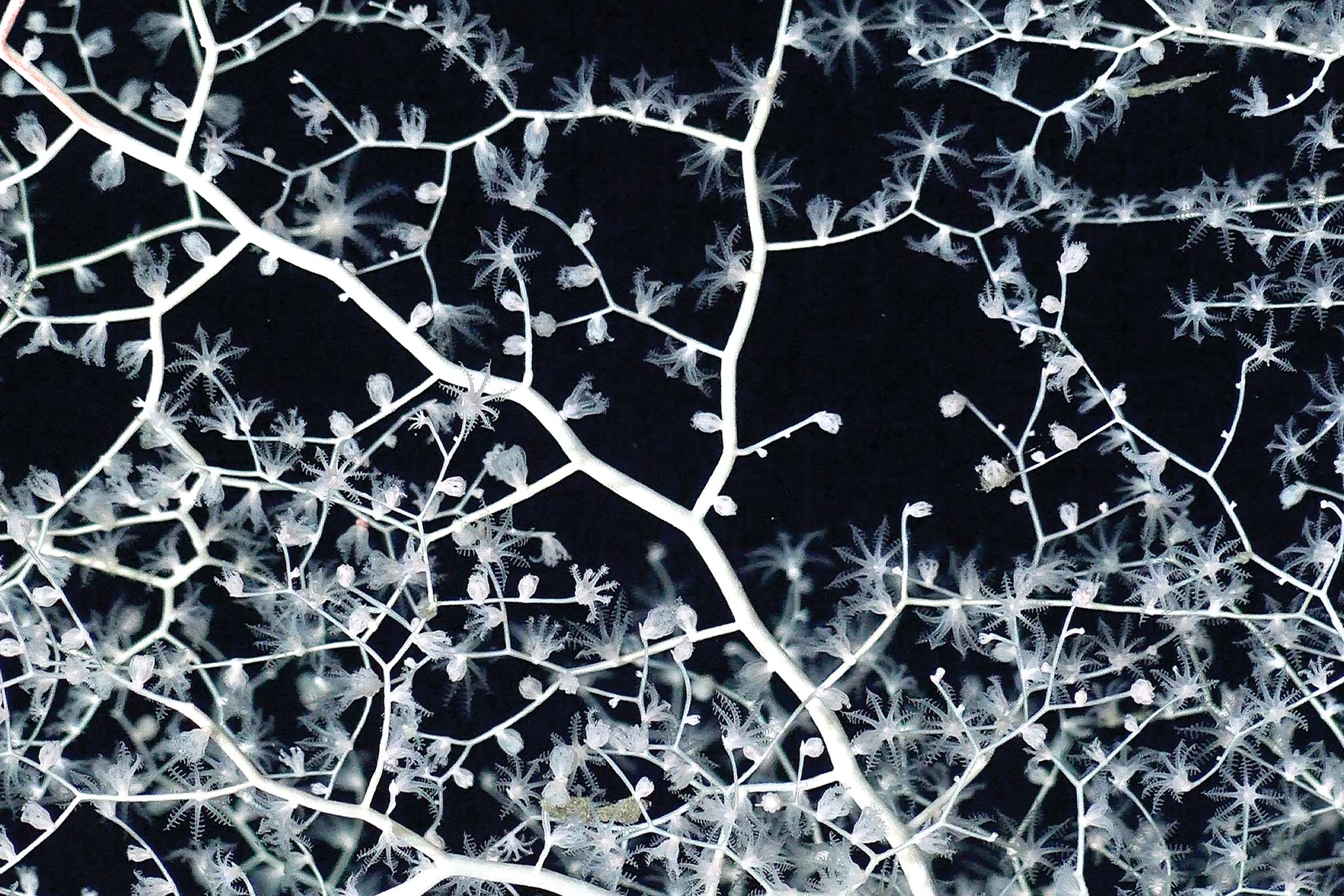

Beyond its newfound cultural relevance, the Santa Monica Airport has also shown much promise and dedication to the future of aviation, particularly all electric aircraft. Though passengers likely won’t fly on zero emissions aircraft until later this year, and battery-powered large passenger jets aren’t expected for another decade, Santa Monica Airport was thinking about and testing demos of electric aircraft as far back as five years ago. It was then that its Airport Association welcomed George Bye, CEO of Bye Aerospace, a pioneer in all-electric flight.

“General aviation is ready for a much-needed boost, and the benefits of electric flight, including lower noise and emissions, are particularly important to airports like Santa Monica Airport,” Bye said in his keynote speech at an event, held in 2018, “Electric Aircraft Morning,” hosted by the Santa Monica Airport Association and Museum of Flying.

The airport’s website continues to post news about the ongoing innovations made in the electric aircraft space and strides companies like Israel’s Eviation are making with its sleek Alice model, and US-based company Ampaire’s continued success with hybrid-electric Cessnas. Typical headlines on this corner of their site read “THE WORLD’S LARGEST ALL-ELECTRIC AIRCRAFT MADE ITS FIRST SUCCESSFUL FLIGHT!” and “THE FUTURE IS ALREADY HERE!” (All caps and exclamation marks are theirs.)

Such enthusiastic declarations hint that, though the end is near, a less noisy, less polluted future might have been possible.