Text by Anne Wallentine

Images by Tim Aukshunas and courtesy of Santa Monica History Museum

Santa Monica Canyon—a swanky, secluded neighborhood nestled between the bluffs of Santa Monica and the Pacific Palisades—is dotted with architectural gems. But long before its residential iteration, the canyon’s lush landscape served as rural rancho land and bohemian beach enclave…with some Hollywood stars thrown in. Today, its eclectic architecture includes everything from Tudor houses to contemporary bungalows, revealing both the area’s history and the influence of famed modernist architects that include Richard Neutra, Ray Kappe, Lloyd Wright, Charles Moore and Craig Ellwood.

The canyon was first colonized via Mexican land grants. In 1839, the Mexican government granted the Marquez and Reyes families the 6,656 acres of Rancho Boca de Santa Monica, which included Santa Monica Canyon, parts of the Palisades, and Topanga. “Thinking of 1849 when this very, very valuable real estate was just grasslands is very, very amazing to me,” says Colleen McAndrews, a local resident and attorney who worked with Marquez descendants to preserve the family’s cemetery in the canyon. Though none of the early adobe houses remain, the footprint of the first Marquez home—believed to be the first permanent structure in the canyon—is marked out in the family’s private plot. American settlers soon followed, bringing new architectural styles to the landscape as it was divided and sold off by its inheritors.

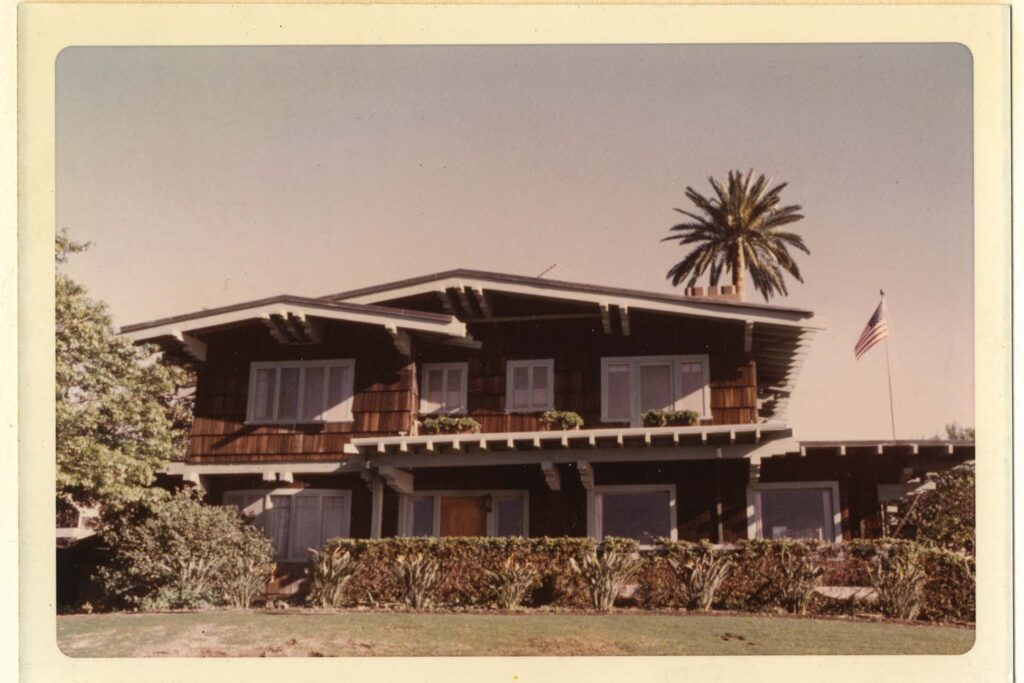

Adelaide Drive runs along the Santa Monica side of the canyon, with sweeping views over it and the ocean. The homes there, some clinging to the edge of the palisade, provide a stroll through architectural history. The son of Senator Jones, one of the modern city’s founders, built the turn-of-the-century Colonial Revival home that is now known as the Second Roy Jones House at 130 Adelaide. Just down the street, the Millbank House embodies the classic California Craftsman ideals of handmade workmanship and natural materials. Further on, architect Frank Gehry’s contemporary home is sustainably-heated, wood-beamed, and glass-paneled—and represents a marked evolution from his first, avant-garde house on 22nd Street, which was made of corrugated metal, glass, and chain-link fencing.

Even beyond Adelaide, the canyon’s mix of construction represents a wide range of regional styles: French Provincial, mock Tudor, and Spanish Mission—like architect John Byers’ sprawling, landmarked Spanish Colonial Revival Bradbury House, built in 1922 on Ocean Way. The unique Mayan- and Pueblo-inspired Zuni House nearby shows the ways these historic styles were romanticized and adapted to the Southern California landscape in the 1920s.

In this period, the canyon began evolving into a freewheeling artists’ and writers’ colony. The 1930s were “a magical time here,” McAndrews says. “It was very much a beach community with small lots and small houses, by and large…It was very bohemian. There were a lot of artists and Hollywood people,” drawn by the landscape and its (then) affordability.

There are no stars lining the sidewalks, but Hollywood legends still linger in the quiet streets. The canyon was home to early movie star Leo Carrillo as well as actress Dolores del Rio and her husband, MGM art director Cedric Gibbons. Silent movie star Ramon Novarro inhabited the Second Roy Jones House for a time, while producer Louis B. Mayer, co-founder of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), owned a vacation home on Ocean Way. Mexican tenor Jose Mojica’s home hosted numerous parties during his ownership and, later, that of Dr. Clifford Loos. Dr. Loos’ sister, screenwriter Anita Loos of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes fame, brought writer friends like Aldous Huxley to visit.

Screenwriter Salka Viertel’s European-style cottage at 165 Mabery Road was another hotspot for the era’s leading artists and intellectuals as she hosted the German émigré community fleeing Nazi repression. Her famed salon included actresses Greta Garbo and Tallulah Bankhead, playwright Bertolt Brecht, and director Billy Wilder. Viertel’s home was later owned by director Gordon Davidson and his wife Judi. McAndrews relates that a young, “brand new architect who didn’t have a lot of work” redid their garage: Frank Gehry. (The practical structure did not reflect his idiosyncratic mature style.)

Writer Christopher Isherwood also orbited the canyon’s literary and celebrity circles, living in several local homes before settling on Adelaide Drive with his partner, artist Don Bachardy. Isherwood enshrined the canyon’s topography and status as an immigrant and LGBTQ+ haven in his 1964 novel A Single Man, where he characterized it as “a subtropical English village with Montmartre manners: a Little Good Place where you could paint a bit, write a bit, and drink lots.” Its residents, he wrote, “saw themselves as rear-guard individualists, making a last-ditch stand against the twentieth century.…They were tacky and cheerful and defiantly bohemian, tirelessly inquisitive about each other’s doings, and boundlessly tolerant.”

After World War II, the canyon’s terrain provided an ideal canvas for the experimentation of the midcentury modern Case Study architects. Five innovative homes were designed on a parcel on Chautauqua Boulevard for the program dreamed up by Art and Architecture magazine’s publisher John Entenza, serving as ‘case studies’ to meet modern needs and soaring post-war demand. These included the Eames House by famed, married designers Charles and Ray, the Entenza House, designed by Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen, and the West House by Rodney Walker. Entenza was already familiar with the neighborhood, having lived on nearby Mesa Road in a Streamline Moderne home he commissioned from Harwell Hamilton Harris in 1939.

Modernist architects continued to colonize the canyon: Thornton Abell, another Case Study architect, built a home on Amalfi Drive, while Richard Neutra left his thumbprint on several lots. Neutra designed the Sten Frenke House at 126 Mabery Road as well as family homes at 491 and 302 Mesa Road, the latter moved there in the 1960s from a previous site. Ray Kappe, founder of the Southern California Institute of Architecture, built homes on Hilltree and Latimer Roads: one a streamlined, set back wood-and-glass treehouse, the other replete with towering steel and concrete curves. The Charles Moore Foundation now preserves the architect’s Burns House on Amalfi Drive, with its sunset palette and dramatic music room.

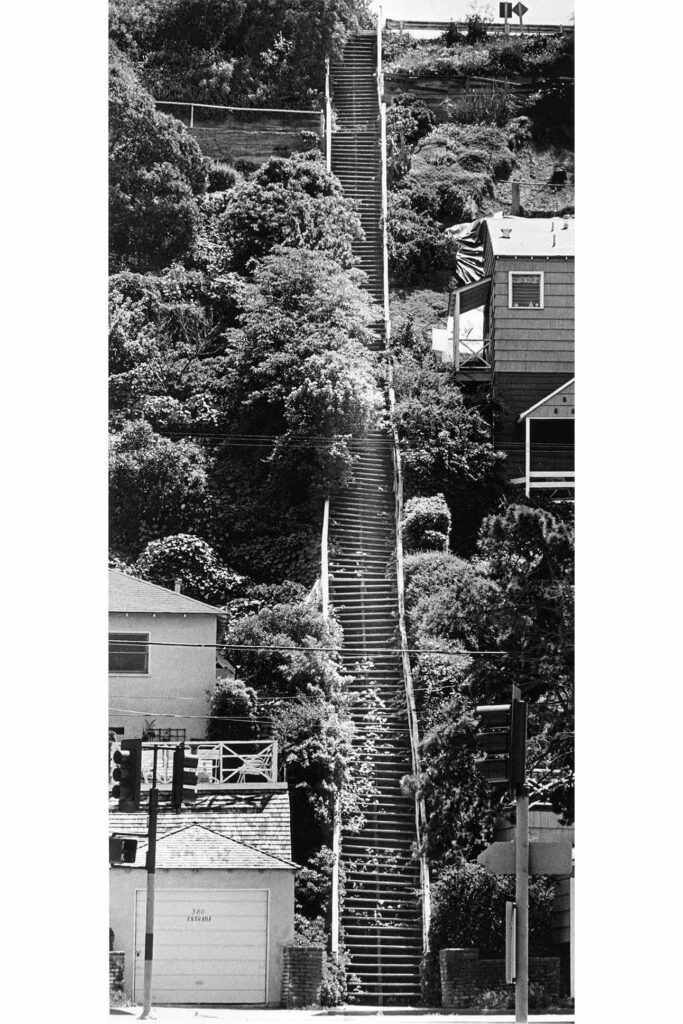

Resident and real estate agent Frank Langen says his first impression of the canyon in childhood was of its wooded, almost rural nature. The neighborhood was “built within these large sycamore trees, and they really dominated the whole experience beyond the architecture,” he recalls. It’s not for nothing that part of the area is still called Rustic Canyon (though the distinctions between the two canyons, and the ‘upper’ and ‘lower’ canyons, are often elided outside of locals and real estate listings). The neighborhood’s architecture is necessarily responsive to the canyon’s slopes—including the “secret stairs” that traverse some of the palisades between streets. Today, one set that runs from Adelaide to Entrada Drive is a popular exercise spot.

The canyon continues to be a “hotbed” of “famous artists, writers, and architects,” Langen says. Its topography “makes it difficult for developers, so it still appeals to individuals that are creative.” New construction continues the canyon’s architectural evolution, alongside efforts to preserve some of the historic structures. A new generation of affluent residents is already shaping the next era of the canyon’s history. They are, Langen says, “the lucky stewards of one of its chapters.”