Text by Lyra Kilston

Images by Sam Muller

Archival images courtesy of Atelier Editions

Falling asleep while lying in the sun’s warmth is a simple but rare pleasure in the churn of a busy life. It is an unmooring from your endless list of tasks, a pause from worries, a luxurious surrender to repose in the middle of the day.

Years ago, I spent a winter with my grandmother in Los Angeles to escape the gloomy drizzle of Washington state. I worked at night, so I slept late every morning and then had breakfast outside, where I lay on a striped blanket and read a Henry James novel. Her backyard was typical for Southern California—tough grass, the drone of leaf blowers, and the sweet-tart scent of citrus trees. Day after day, I’d read until I felt like laying my head down on my arms to drift off. I recall the prickly blades of grass beneath me, the rich reds and golds across my eyelids, the steady heat on my back. The feeling of coming up to consciousness incrementally, layer by layer. I may have forgotten those eventless mornings, except they came to represent an unusual period of calm and wellbeing, a wealth of time and warmth.

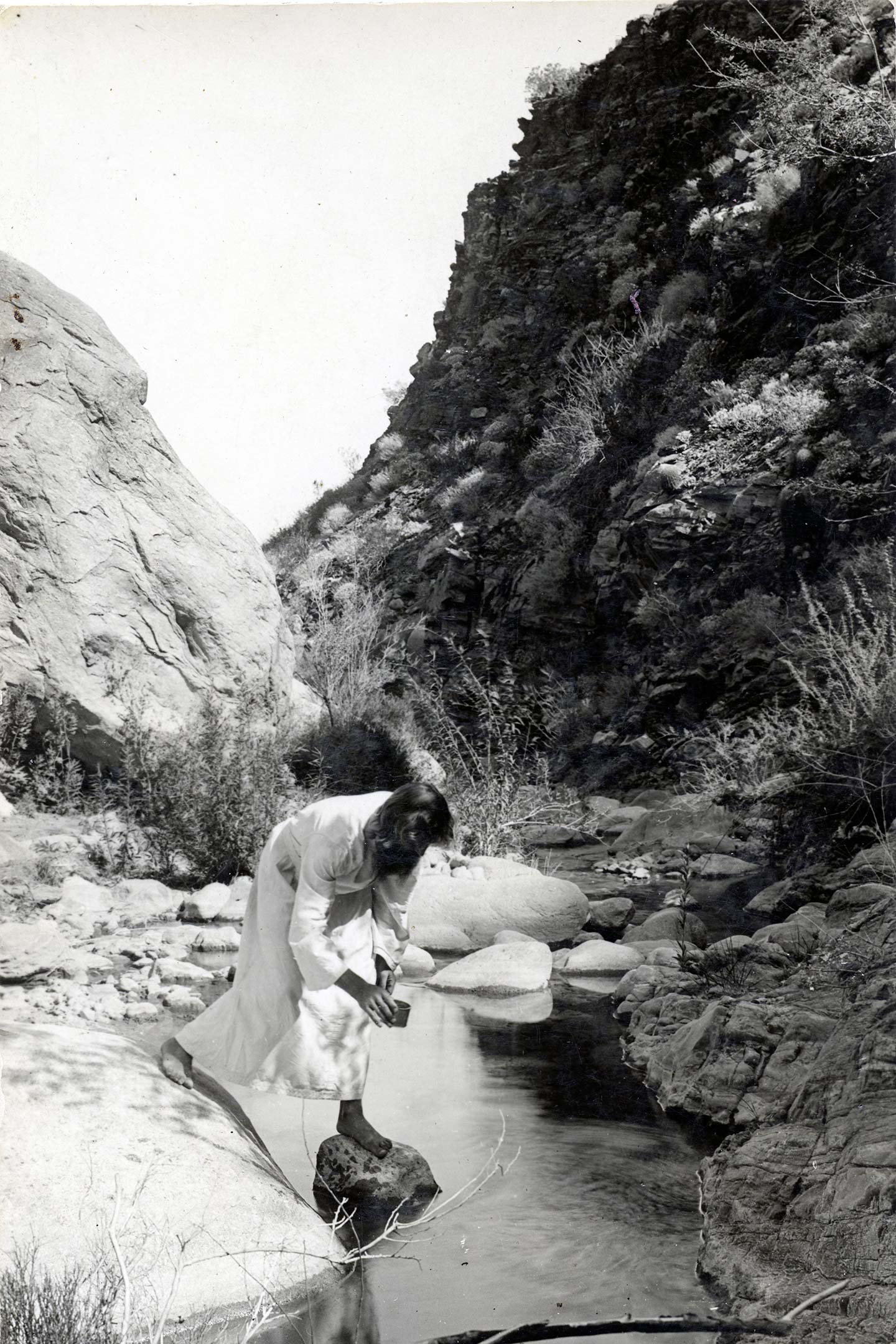

Lying in the sun was once considered medicinal. Sun cures, or heliotherapy, were used to treat a variety of illnesses and strengthen the bodies of those who were at higher risk of contracting diseases like tuberculosis or cholera. In the late 19th century, doctors began prescribing sun exposure in measured doses. If there wasn’t enough strong sun and fresh air where you lived, they would suggest traveling elsewhere to pursue a “medico-geographic” cure. To the sanatoriums of the Swiss Alps, perhaps, or to the American Southwest. Thousands of health seekers also flocked to Southern California to partake in the benefits of its celebrated climate. Many stayed permanently, shaping the region’s health-oriented culture—an eccentric history I explore in my book Sun Seekers: The Cure of California.

Climate and location mattered greatly, but so did architecture. Doctors and public health officials in the late 19th century noticed that rates of fatal illness were far worse in urban areas where people lived crowded together in dim, damp housing and worked in unventilated factories. These buildings, with their meager windows and poor air circulation, were deemed a public health crisis, and medical professionals worked closely with architects and urban planners to implement more salubrious designs that invited “Dr. Sun” inside.

At the same time, the sanatorium movement was spreading from the mountains of Europe to the United States. A cross between a hospital and a resort, sanitoriums were located in pristine rural settings, offering true retreat from the strains of city life. Some of the earliest were designed to resemble grand hotels, with towers and turrets, opulent curtains and rugs, and walls of thick stone.

But as belief in the healing properties of sunlight and fresh air gained popularity in the early 20th century, the design of such buildings began to change. It wasn’t enough to seek health outdoors; the outdoors also had to be brought inside. In Davos, for example, new sanatoriums were built facing the sun, with large windows intended to stay open day and night. Rooms were fitted with French doors leading to balconies and terraces so patients could be rolled outside in their beds to take their sun and air cures beneath heavy fur blankets. When the German novelist Thomas Mann wrote about a Swiss sanatorium in his book The Magic Mountain, he described the many-balconied buildings as being “so porous as to resemble a sponge.”

House design followed suit. Sleeping porches were added to bedrooms for outdoor rest, and large uncovered windows, balconies, and terraces brought the cures of nature to domestic spaces. Interiors became more health oriented as well. The dark and stuffy Victorian-era parlor gave way to a clean, modern style. It wasn’t just aesthetic—white walls were considered more sanitary, and easily washable surfaces were preferred.

In Southern California, the health seekers and doctors of all stripes who came to treat them forged a famed lifestyle that transformed diet, exercise, and living space. While the constant sunshine and mild weather were considered healthful on their own, they also enabled evolving architectural styles to further blur the line between indoors and outdoors.

I’ve visited the sleeping porches of Pasadena Craftsman houses, where turn-of-the-century residents set up their beds outside to imbibe the night air. And I’ve sat in dappled shade by a hearth in an outdoor living room of the pioneering Schindler House in West Hollywood. When the house was completed in 1922, a year before the Hollywoodland sign was mounted, its bohemian residents slept under the stars on the house’s flat roofs.

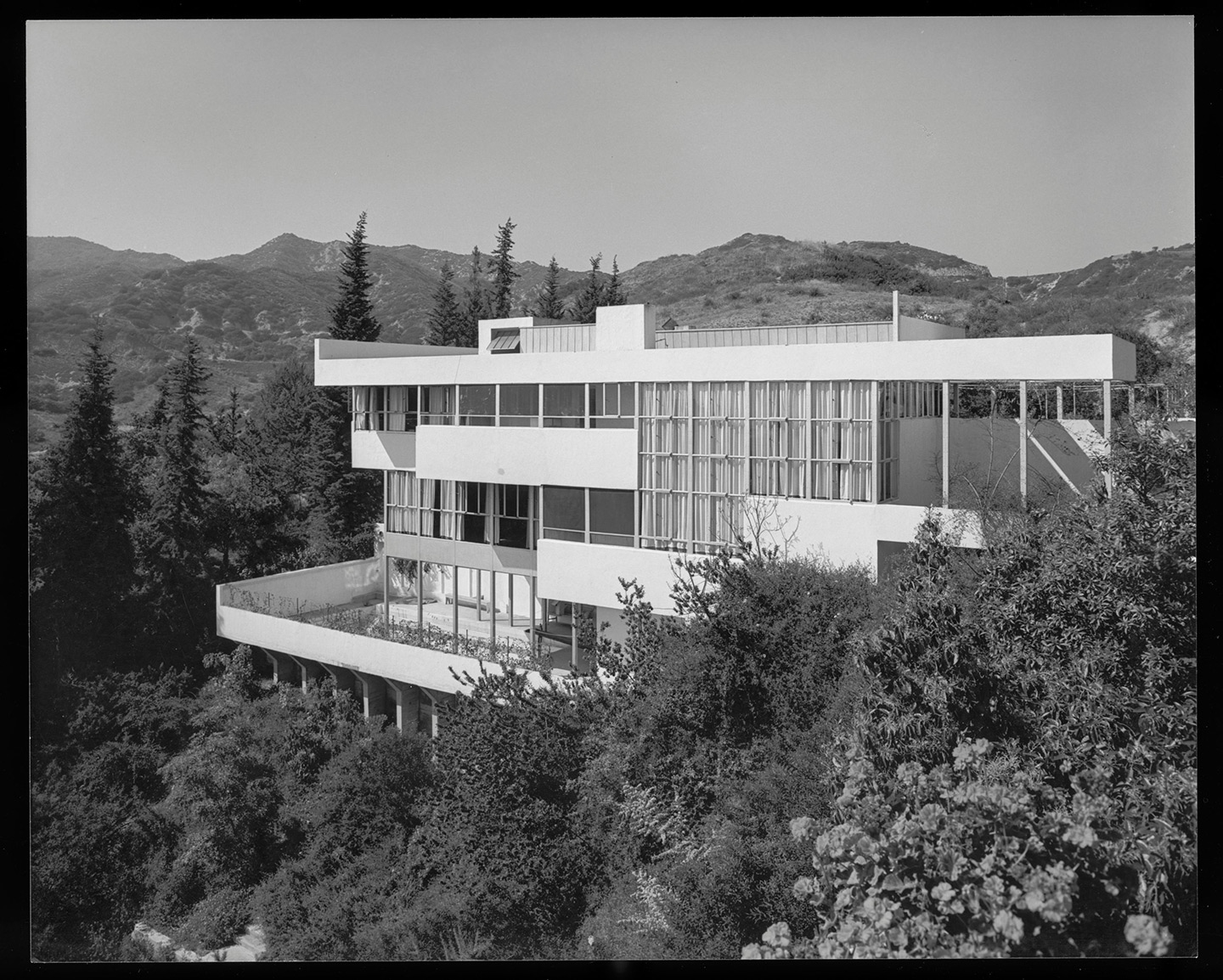

The idea of a health-giving house reached its apex with the Lovell Health House, completed in 1929 in the Hollywood Hills. Built for Philip Lovell, a vegetarian naturopathic doctor and health evangelist, the house stands as a monument to the benefits of living among the natural elements. Designed by Austrian émigré architect Richard Neutra, who helped import European modernism to the West Coast, the sleek home of seemingly floating white planes features huge walls of glass facing the sun. Each bedroom opens to a private sleeping porch for nighttime slumber and therapeutic nude sunbathing, while a pool, exercise equipment, and an outdoor classroom in the yard were part of the daily regimen of the Lovells’ three sons. Lovell boasted that no one in his family ever needed conventional medical care—their permeable, sun-drenched house and outdoor lifestyle were treatment enough.

The Health House still stands, about 20 minutes away from where my grandmother lived. I’ve experienced the strength of the afternoon sun as it pours in through its tall windows, gazed at the hills from its porches, and walked around its now-empty pool, imagining the optimism and fervor of a distant time. It was a startlingly radical house when it was completed, but its design strongly influenced the look of California’s midcentury modern homes, with their flat roofs, glass walls, and poolside living.

During that youthful winter at my grandmother’s house, I didn’t know any of this history. I just knew that taking a sun bath felt incredibly restorative. Now, when I drive by glassy modern houses in the hills or bicycle by their descendants on the beach path, I like to think of Southern California’s early days as a beacon of healthful outdoor living. And on the occasions that I can steal a bit of time to recline in the afternoon light, I recall those health seekers, faithfully taking their daily doses of healing sun.