Text by Alex Norcia

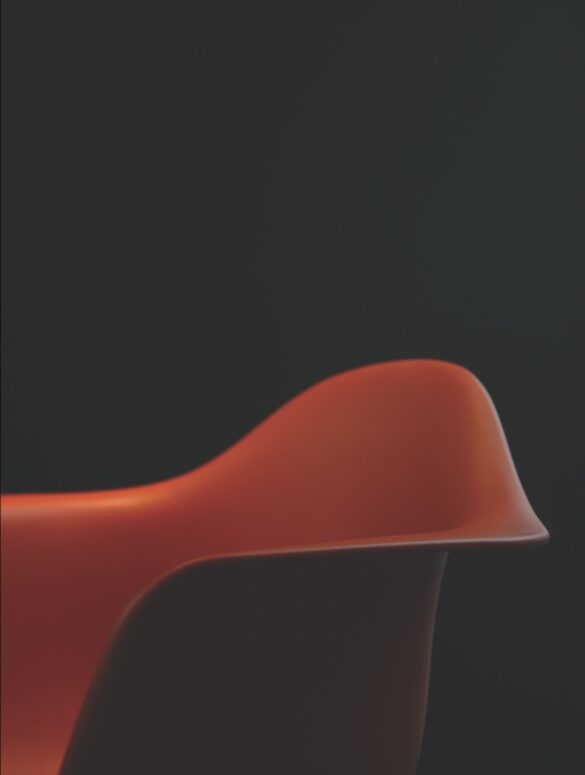

Images by Thula Creative, Dennis Scherdt, and Juan Miguel Agudo

The Eames House, located in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles and often heralded as a landmark of mid-20th century modern architecture, rests atop a bluff that’s high enough to see the ocean in the distance. Charles and Ray Eames, a married pair of American industrial designers, moved in on Christmas Eve 1949 and stayed until the end of their lives. (Charles died in 1978; Ray in 1988.) The home, which they built as part of a program meant to encourage affordable modern housing, features exposed steel and a number of sliding glass doors that open to the outside, where wildlife teems around fresh-smelling eucalyptus trees.

It also, on a limited basis, fills with people. The place has become something of a mecca for appeciaters and lovers of modern design, as the younger generations of Eames have kept it maintained for the public.

The structure now stands as a National Historic Landmark and museum, offering a number of tours throughout the year. Guests, who should certainly plan ahead if they cared to visit, pay $30 for an exterior showing of the grounds and an occasional peek into a window, where they can view the couple’s meticulously curated art. If you choose, you can also schedule an interior tour, running at $275, or $225 for members, for one to two adults and $450, or $400 for members, for three to four adults.

I always compare the Eames Lounge Chair to a Rolex watch.

Ryan Hobbs

The Eames House is, in no small part, tantamount to the legacy of Charles and Ray, the former of whom said the role of a designer as “a very good, thoughtful host anticipating the needs of his guests.”

Based largely in Los Angeles, Charles, an architect, and Ray, a painter, had polymathic careers, where for decades they complimented each other, allowing their respective creative aspects to shine through, and made significant contributions not only to furniture designs, but to communications, filmmaking, art, and photography. They had the confidence, emphasized Pat Kirkham, a professor emerita at Bard Graduate Center and the author of Charles and Ray Eames: Designers of the Twentieth Century, to follow their own interests and seemed to only take on work that they really wanted to do.” It’s a luxury, perhaps, that’s not afforded to every designer.

“Their legacy has always been changing,” she says. “A lot of the questions I get from students now are much less technical than when I was teaching in, say, the 70s. Today, I think much more the legacy is around ethical use and integrity. It’s about quality at the end of the day. Like the notion of truth to materials and honesty to construction—doing something very well in the appropriate manner.”

Beyond that, they developed a reputation as the good “hosts” Charles once described. Quite literally: They constantly entertained friends and family and took a real joy in their labor and creation, in a way expanding an arts-and-crafts theory from the mid-to-late 1800s popularized by the textile designer William Morris. “They took your pleasure seriously,” Kirkham says. “Maybe a better way to put it is that they took pleasure in the serious parts of their lives. They had the ability to make everyday occasions very special.”

For them, designing—and the pleasure they derived from it—didn’t stop. “The design process for Chales and Ray never ended in manufacturing,” Eames Demetrios, a grandson of Charles and Ray and the current director of the Eames Office, said during a TED Talk. “It continued. They were always trying to make things better and better.”

“They didn’t obsess about style for style’s sake,” he later added. “They didn’t say our style is curves; let’s make the house curvy. They didn’t say our style is grids; let’s make the chair gridy. They focused on the need. They tried to follow the design problem.”

As mid-century furniture has had a kind of revival in the past few years, so too has consumers’ fascination with Charles and Ray’s work, particularly the series of Eames Lounge Chairs and Ottomans they constructed during their lives. Certain versions of chairs, which the couple fussed with over the decades, can fetch thousands and thousands of dollars in the secondary market. (Some of them are even exhibited in New York’s Museum of Modern Art.)

The demand for the Eames Lounge Chair became so high that Ryan Hobbs, a former high school teacher, quit his job to restore them and other mid-century modern furniture full-time. Hobbs, the owner with his wife Nicole of Hobbs Modern, a mid-century modern furniture dealer and restorer in San Diego, had no formal training in furniture restoration. But an admirer of Charles and Ray, especially their eye for precision, sparked a passion that turned into his vocation. Eventually, he approached a local furniture restorer in San Diego who, on the brink of retirement, agreed to teach Hobbs the trade. He never looked back.

“Every component of the Eames chair was just built really, really well,” Hobbs says. “The Eames bases were all sawed aluminum, so we sometimes polish the aluminum to factory chrome shine. The wood shells can take a day to sand. And then putting shock mounts on the chair, which are super precisely put in.”

Hobbs searches for his own chairs to buy and restore, and he also has clients who approach him for custom restorations. He’s constantly on the lookout for Eames chairs, scouring Facebook Marketplace, Offer Up, auction houses, and estate sales.

“I always compare the Eames Lounge Chair to a Rolex watch,” Hobbs says. “It’s an item that, once you’ve made it in life, you’re like, ‘I want one of those.’ Today, I can probably get $4,000 more for an Eames Lounge Chair than I could only a few years ago.”

Hobbs spends more than 30 hours restoring a given chair, and estimates he has already restored more than 100 with no likelihood of slowing down. He has never enjoyed working more in his life. The whole process, he says, is a joyful one. It’s a pleasure taking other people’s pleasure seriously.